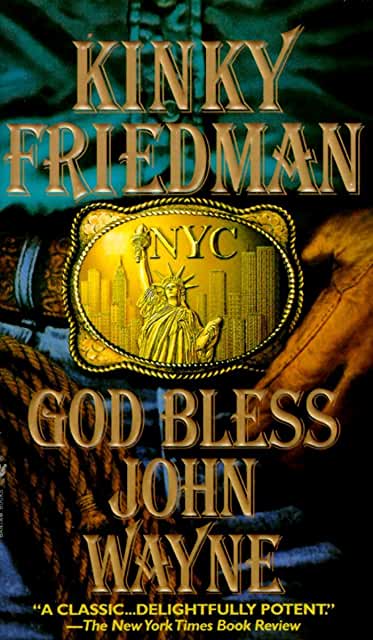

Last week I had lunch with a friend who had just turned 71, my own age. We talked about the absolute bizarreness of being 71, and shared thoughts about what future might be left for us. Afterwards, we went into his music studio (he’s a piano teacher and gifted and accomplished pianist), and I noticed a book by Kinky Friedman on his bookshelves.

If you don’t know Kinky Friedman as an author, you might have heard of him as a country singer. He named his band Kinky Friedman and the Texas Jewboys; one of his big hits was a parody of “Proud to be an Okie from Muskogee” called “Proud to be an Asshole from El Paso.”

If you don’t know Kinky Friedman as an author, you might have heard of him as a country singer. He named his band Kinky Friedman and the Texas Jewboys; one of his big hits was a parody of “Proud to be an Okie from Muskogee” called “Proud to be an Asshole from El Paso.”

As you can tell, Kinky is not a serious, straight-laced kind of guy.

But he has a series of terrific, hysterical mystery novels that I read and loved. His detective is a former country music singer named “Kinky Friedman,” who lives in Greenwich Village and hangs around with a group of friends whose names are the same as the real Kinky’s real group of friends (Ratso, Rambam, and so on). The books are rife with Kinky’s brand of wry, post-modern, satiric humor.

I remarked on this book on my friend’s bookshelves, and we started talking about his library. When I took a closer look at his shelves, I noticed they looked a lot like my bookshelves—albeit his were a lot neater than mine. We shared the exact same taste in authors . . . there was Last Exit to Brooklyn, there was Nabokov, Joseph Conrad, Jerzy Kosinski, Thomas Mann, Tolstoy, Updike, Solzhenitsyn, and many, many more books that I also owned.

On its face, this wasn’t surprising; after all, we were very similar, my friend and I, with similar backgrounds and life experiences.

There was even one of my own novels on my friend’s shelves, along with a book by his brother, who had written some historical mystery novels published in the 1990s by St. Martin’s Press.

My friend described his writer-brother as an alcoholic failed writer, and holding his book in my hands I said, “Not that there’s anything wrong with being a failed writer . . . Half the people in this room are failed writers!”

We both laughed. But like Kinky Friedman’s books, it was funny in part because I was being deadly serious.

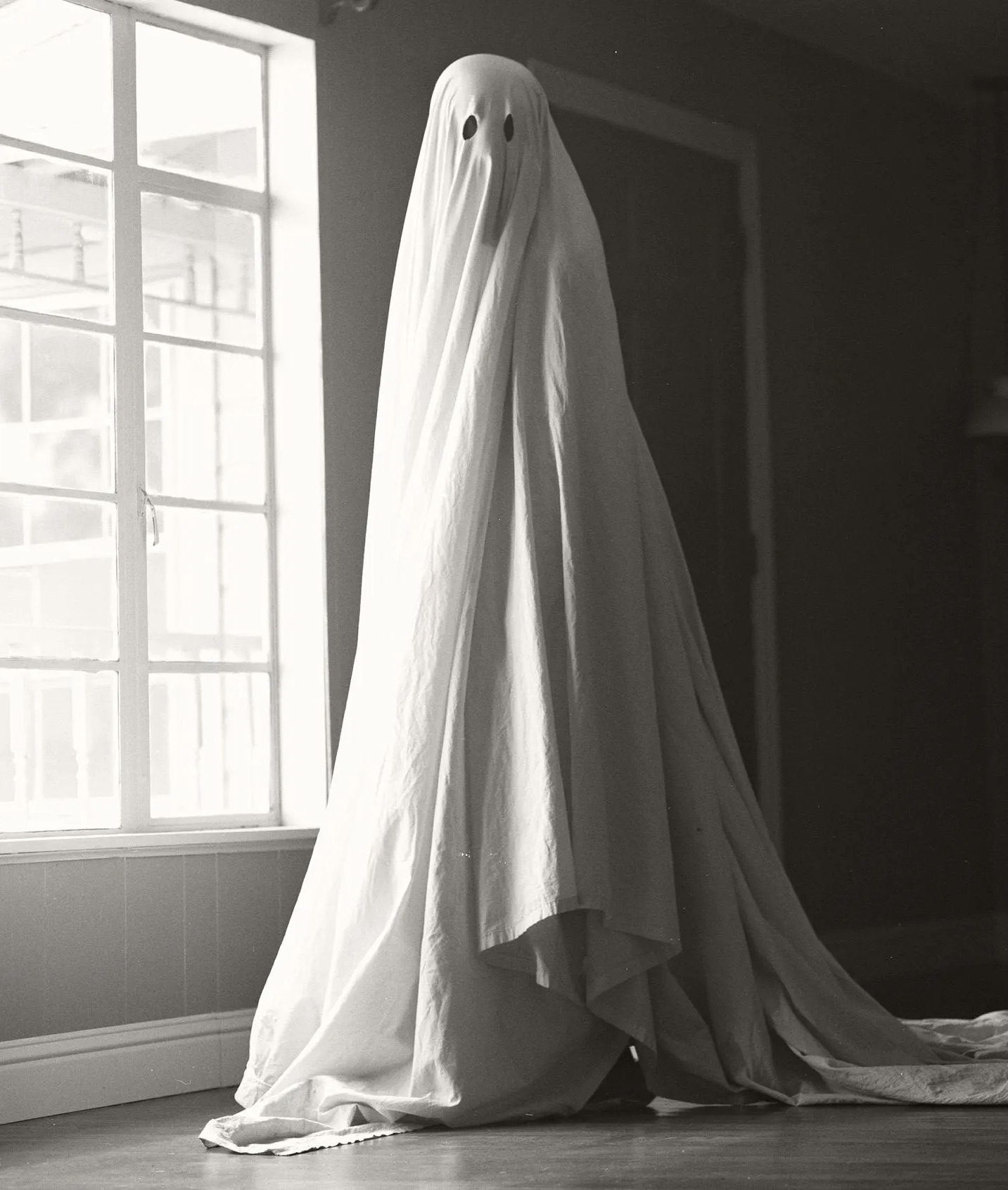

Like most creative people, I’m never more than half a step away from the phantoms of failure. Too often I feel their cold breath on my neck, their ghostly arms holding me back.

In my friend’s studio, in view of all these books from authors whom I had once devoured as a young man, and whose works so influenced my own intellectual development, the specters arose again. With our lunchtime discussion of aging fresh in my mind, I told my friend, “This makes me feel nostalgic for the time when I discovered all these writers.”

Thinking about it later, though, I understood that what I was actually nostalgic for wasn’t the young man who had yet to discover these great writers. Rather, it was for the future that young man imagined . . . a future as a writer, a future that lay ahead, open, waiting to be lived, containing a sense of promise that I remember hoping for and in an important way relying on to get me through the difficult times of my youth.

An as-yet unfailed-in future.

On a visit to New York City in the 1970s, when I was in my twenties, I went into the famous Gotham Book Mart and wandered around practically open-mouthed at the literary life that storied store represented for me, with stacks of books by Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Faulkner, Ellison, Flannery O’Connor, Kerouac, Graham Greene, Dos Passos, and other classic works of fiction and philosophy from America and Europe, as well as what was then the cutting edge of the literary life . . . . Thomas Pynchon, Joan Didion, Saul Bellow, Allen Ginsberg, Susan Sontag, John Barth, John Barthelme, Kurt Vonnegut, and others.

Even now, so many years later, I remember thinking, “This is the life I want to live.”

Except in the end I didn’t.

Today, as I contemplate my gathering senescence, that future I imagined exists only as a nostalgic memory of possibility, not as a remembered past.

I tried. I paid all the dues you’re supposed to pay, including collecting rejections by the score, along with enough acceptances to keep me going. And then, in the early 80s, a hotshot New York agent agreed to represent a novel I’d written. He was the real deal, and I thought it was just a matter of time until I broke through.

Except in the end it wasn’t.

After three years of trying to place it, the agent regretfully sent the manuscript back, saying he couldn’t do anything more with it. Nobody wanted it. He didn’t want it. And he turned down the novel I’d written in the meanwhile.

I was crushed. That final rejection was it for me. I’m not meant for this, I thought. I failed.

I left imaginative writing behind. I became a writer, yes, a professional, earning my living by my pen (or word processor, as the case may be). But what I wrote were speeches, grants, newsletters, annual reports, video scripts, and everything else you can think of for hospitals, government, and businesses as big as IBM and GM and as small as one-man computer start-ups.

A body of accomplishment, to be sure. But not as a writer, with all that had represented for me. I was good at knocking out speeches on the AIDS epidemic in New York City, but not writing novels about the moral life of the universe.

It was impossible not to agonize over why I failed. Lack of talent hit me like a pie in the face, of course. Some have what it takes, some don’t; I was the latter.

Other explanations arose the more I thought—and agonized—about it . . . explanations like bad luck (another agent wanted to represent that early book but she died before anything could happen); ambivalence about the end goal; a prideful unwillingness to do the kind of sucking up I perceived I needed to do, and the concomitant lack of a mentor helping me along; the need to earn a living; a low (and lowering) self-image that wouldn’t let me consider that I actually had what it took to find a place for myself in the world where I wanted to live, along with a pathological shyness that kept me from promoting myself more aggressively, a dangerous combination; perhaps an abiding timidity that kept me from screwing my courage to the sticking place when it most mattered.

Perhaps ultimately a combination of all of those.

Whenever I felt the urge to write imaginatively (which, by the way, was relentless), the memory of having failed so spectacularly stopped me. Nobody wants what you have to say, my inner demon insisted; just stop already.

During that time, I wrestled almost constantly with what success as a writer really meant. I tried to pinpoint what it was that I had failed at.

Eventually, I became a college professor, and, a decade after I stopped creative writing, I realized I needed to start again. The pressure to create grew too insistent to ignore. After all that time, I was still smarting from failing as a fiction writer, so I began writing poetry, which I hadn’t failed at yet.

And then to my surprise, people began to publish my poems. One poem won a prize. Then I wrote and published some short stories and one of them won a prize.

Finally, I tried my hand at another novel, and wrote a series of mystery novels. I just published my seventh. I published two slender collections of poetry.

So am I a success? By some measures, yes. I kept at it; I didn’t quit; I started back writing again, itself an act of both defiance and liberation. I became an independent author and took the means of production back into my own hands.

By other measures, no. I published all the novels myself, under an imprint I created, which meant no authority has validated me as a writer (Mystery Writers of America doesn’t even consider me a real mystery writer); the poetry is published on the Internet and tiny journals, with the books from two miniscule presses, neither of which even exists anymore. Reviews are few and far between; my work is invisible to prestigious reviewers. Despite my best efforts, each novel I publish sells fewer copies than the one before.

So am I a failure?

That question will never go away. I always tell people it’s the work that matters, not the sales or the reception, but secretly in my heart I know I don’t believe that. I think most creative people don’t.

Everybody knows Shakespeare’s lines about there being “a tide in the affairs of men which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune.” What often gets left out is the end of the quotation: “omitted, all the voyage of their life is bound in shallows and in miseries.”

Even now, I’m not sure I ever saw that tide. If it came in, it feels like I never took it.

I won’t say the voyage of my life has been bound in miseries—on the contrary, it’s been extraordinarily fulfilling in a variety of ways. But looking backward, as I was doing in my friend’s music studio, face-to-face with the reminders of a future that was as yet unfailed-in—it’s impossible not to fear that my life as a writer—the life I had wanted to live—has been bound in the shallows. And that I’ve been spent my time splashing around, near the beach, while others are out in deeper waters.

“Our doubts are traitors,” says Shakespeare. Unfortunately, they are often our best friends, too.

Several years ago, I was thinking about Bob Dylan and his own journey. We like to believe that talent will out, and so his fame and fortune were inevitable. But I started to think about what would have happened if, by some combination of misfortunes, he had never made it. I wrote a poem about that, which binds up some of the ideas I’ve touched on here. The poem imagines an alternative history for Dylan. What if he had never made it when he moved to New York, the poem asks.

What if all the breaks had gone against him?

What if he had failed?

At the Red Lobster in Duluth, MN*

He left behind the frozen landscape

and empty mines of his upper Midwest home

to head east, for New York City

where he heard it all was happening.

At every stop on the way to the Port Authority

he jumped out to grab a smoke

and check on the heavy battered Gibson

riding in the luggage compartment

beside his big suitcase. In between

he took in the fields and crossroads

on the freedom highway of the vast country.

When he landed in the city

he walked happily down Eighth Avenue

through the smells of pickles and pizza

to locate himself in a railroad flat

on the sixth floor of a walkup

where he shooed away rats on the stairs.

Most nights he made the rounds

of the folk clubs in the Village

singing in his rough raspy voice

the songs he had written on the backs

of invoices from his father’s store.

Nights when he wasn’t singing somewhere

he spent soaking in the tub

in his kitchen and dreaming of the future.

But the gigs got shorter and came less often

and he started getting to parties

after the important people had left.

The record company stopped returning his calls

and one day a club owner told him, “Kid,

I’ve seen it all, and you just don’t have it”

just as his money ran out

and rather than ask his father for more

he took the A train back uptown

but not before leaving his guitar at the Salvation Army

on Spring Street at the corner of Lafayette

and twisting his harmonica rig

into the shape of the state of Minnesota

and dropping it in a trash can on the street.

Though his friends begged him to stay

he jumped on a Greyhound back to the north country

where he learned how to cook

or at least defrost and reheat fish

at the Red Lobster in Duluth.

He gave up listening to music at all

though occasionally lyrics formed

unbidden in his head

as he stood over the big stove

turning flounders that smelled of butter.

He hummed these secret tunes to himself

growing old behind the cries of the servers

clamoring for their orders.

*A version of this poem was published in Shaking Like a Mountain, March 2010.

If you don’t know Kinky Friedman as an author, you might have heard of him as a country singer. He named his band Kinky Friedman and the Texas Jewboys; one of his big hits was a parody of “Proud to be an Okie from Muskogee” called “Proud to be an Asshole from El Paso.”

If you don’t know Kinky Friedman as an author, you might have heard of him as a country singer. He named his band Kinky Friedman and the Texas Jewboys; one of his big hits was a parody of “Proud to be an Okie from Muskogee” called “Proud to be an Asshole from El Paso.”

MP: After I retired early from the FPD (thanks in large part to the efforts of Nick Russo, but that’s a longer story), I was at loose ends . . . I wasn’t even fifty, with the rest of my life ahead of me, and didn’t know how I was going to fill my days from then on. An 83-year-old private investigator I had met on one of my previous cases, Manny Greene, had been after me to join his one-man agency. I wasn’t keen on doing that; I thought I should do something else, something new. But when Manny—that wise, wise fellow—asked me to look into the disappearance of a young man who hadn’t been seen for forty years, I realized (as I’m sure he knew I would) that investigation is what I was best at. So I joined his agency, and one afternoon when he was tied up and unable to keep a meeting with a new client, he asked me to speak with her. She wanted to find out how her brother wound up strung out on drugs at a skeevy motel in Ferndale, so the Ferndale connection got me hooked and this book was off and running.

MP: After I retired early from the FPD (thanks in large part to the efforts of Nick Russo, but that’s a longer story), I was at loose ends . . . I wasn’t even fifty, with the rest of my life ahead of me, and didn’t know how I was going to fill my days from then on. An 83-year-old private investigator I had met on one of my previous cases, Manny Greene, had been after me to join his one-man agency. I wasn’t keen on doing that; I thought I should do something else, something new. But when Manny—that wise, wise fellow—asked me to look into the disappearance of a young man who hadn’t been seen for forty years, I realized (as I’m sure he knew I would) that investigation is what I was best at. So I joined his agency, and one afternoon when he was tied up and unable to keep a meeting with a new client, he asked me to speak with her. She wanted to find out how her brother wound up strung out on drugs at a skeevy motel in Ferndale, so the Ferndale connection got me hooked and this book was off and running.